Where Did the Third Passover Seder Originate From?

Explore the history of the third Passover seder and how the nuanced tradition plays a part in The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel

By Anthony Mordechai Tzvi Russell

Published Mar 30, 2023

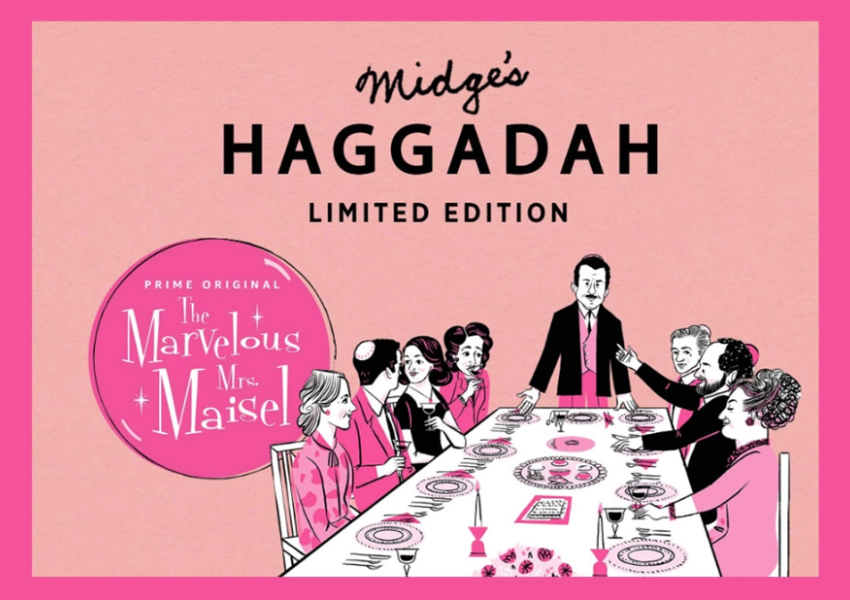

An image from Midge's Haggadah

Once, during kiddush luncheon, I asked a person of a certain age if they had seen the critically-acclaimed period drama television series Mad Men. Their response was immediate: “I don’t need to watch Mad Men, I already lived through it.”

Thanks to the immense popularity of this and another popular midcentury-set television series, American Jews have been able to revisit a critical moment in the history of their assimilation into the greater fabric of American society.

The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel gaily steps into the earlier (and considerably more troubled ) footsteps of the aforementioned Mad Men, whose complicated and conflicted Jewish characters endured a midcentury climate of casual antisemitism, the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust, and existential crises of identity.

The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel takes a somewhat sunnier route through these potentially treacherous historical waters, a choice represented in material form by a Jewish object the show produced in collaboration with Maxwell House Coffee: 2019’s Midge’s Haggadah, a version of the classic Maxwell House Haggadah featuring illustrations of the show’s beloved characters at the seder table, a brisket recipe, and fake stains from the wine glass of a previous year’s seder attendee.

Every year there are new Haggadahs, each one articulating its own vision of renewed liberation as activated throughout the Passover Seder. Amid the upward economic, cultural, and societal swing of the postwar period, what were midcentury seder attendees looking to be liberated from? Having used The classic Maxwell House Haggadah at an in-law’s seder last year, I’m not sure that text has many clues, and Midge’s update seems to supply only pleasantly nostalgic ones.

It turns out that, for some Jews, the image of midcentury seders past is decidedly more different — more radical, more relevant, and, oddly, a little more uptown — than television depictions would lead us to believe. Some of these seders didn’t even happen on the first two nights of Passover — a real break from tradition. Through the memories of Sheila Horvitz, I’d like to introduce you to der driter seyder — “The Third Seder”.

A uniquely American institution stemming from the first decades of the 20th century, the Third Seder reimagined the traditional Passover seder as a kind of mass communal engagement with the themes of the Haggadah through a cultural and labor-oriented leftist political lens. While very much of their time, they anticipated the social justice-themed seders of later decades, most famously, Rabbi Arthur Waskow’s 1969 Freedom Seder, created, in part, as a response to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. the year before.

The Third Seder hails from a time when the form of the traditional Passover seder was not considered to be appropriate or capacious enough to include the present-day struggles for liberation echoed in the Exodus narrative. For that, you needed an additional day with an additional seder with additional people (a thousand of them, apparently!) with additional languages and additional songs filling an appropriate and capacious ballroom at the Waldorf Astoria.

Anthony Russell is a multidisciplinary artist specializing in Yiddish culture.

Reflections

For those who hide the afikomen:

If you were planning a Third Seder for a thousand attendees, what would be its themes? What stories, songs, or readings would you include in your Third Seder?

For those who find the afikomen:

If you could create a Passover Haggadah based on your family’s Passover seders, what would it look like? What recipes, anecdotes, pictures (or food stains) would fill its pages?

For lovers of nostalgia:

How do you imagine present-day Jewish life will be depicted in the entertainment of the future? Do you think you’ll recognize yourself in their portrayals?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox