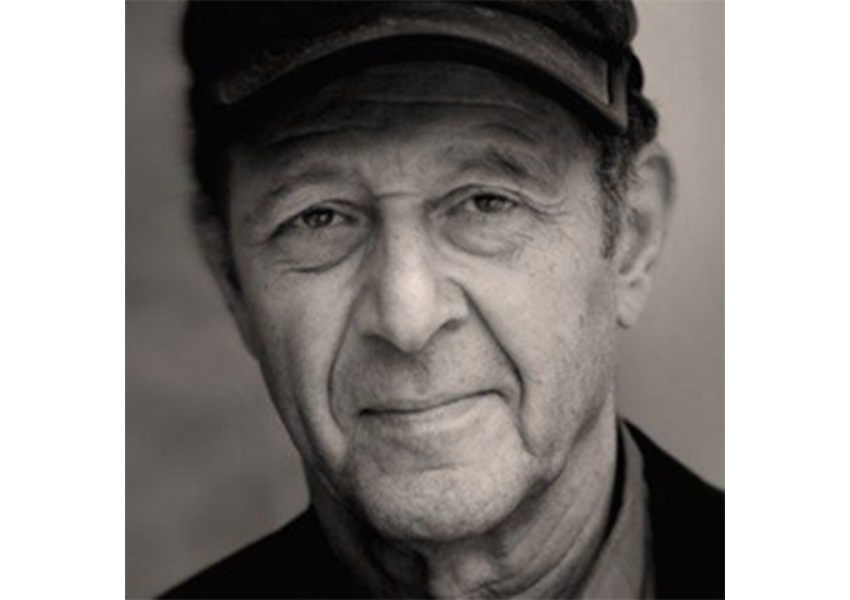

Steve Reich: Listening to a Jewish Composer

He’s been called “the world’s most important living composer” (The Globe and Mail, Toronto), “the most original musical thinker of our time” (The New Yorker), and “among the greatest composers of the century” (New York Times). His music is played across the globe. And his influence has extended beyond the world of “classical music,” impacting rock and pop and countless young musicians and composers.

Steve Reich is also a very serious Jew, a Judaism he came to fairly late in life. Few contemporary composers of his status have regularly used Hebrew text in their music or embraced Jewish concepts for material—yet he has never been compartmentalized as a “Jewish composer”. He is a musician who has had a profound impact on the course of music in the 20th and 21st centuries. And at 86, he’s still working.

Reich’s early career used recordings isolating a spoken phrase in which the recordings were “phased”—two tape loops of the same voice playing simultaneously on two different tape players. Because machines can vary, the voices leave unison bit by bit until they diverge into dense sound and varied rhythms. It’s called “phasing,” As a college music student in the late 60s, I first heard one of the early pieces using this technique, Come Out (1966). It fascinated me and I found his technique groundbreaking. His other piece, It’s Gonna’ Rain, was popular among the avant-garde.

Reich soon turned to live music, played by musicians, using the phasing process in performance and on records. The result relates to the traditional canons composed by Bach with a modern twist. Think of two musicians playing the same notes in unison, then one of the players slowly, but methodically, increases the spacing by a very short moment.

Though both parents were Jewish, Reich had minimal Jewish education as a child, including what he calls a “lip-synch” bar mitzvah where he didn’t understand the words he learned. As his career as a composer grew, he studied African drumming in Ghana (he was a percussionist, after all), and Gamelan music in Bali. Steeped in their rich traditions, he realized that he knew little of his own Jewish traditions, and in his late 30s began to study at the Lincoln Square Synagogue in New York, an avid student with a deep dive into Hebrew, cantillation, and Jewish musical traditions which would influence his music.

In New York, he formed “Steve Reich and Musicians”, a group that played his expansive music in venues across the city. They became popular in Europe as well. He befriended many rising star musicians (he and composer Philip Glass moved furniture together to support themselves, and Reich drove a cab), modern artists like Richard Serra and Sol LeWitt, and musical notaries such as conductor Michael Tilson Thomas. His music, dubbed “minimalism” for its repetitive, shifting tones and patterns, gained larger and larger audiences. His works such as Four Organs, Drumming, and Music for 18 Musicians are complex pieces that were built on melody, harmony, and rhythm, an alternative to the atonal, serial, difficult modern music that seemed the rage at the time.

Three important pieces vividly illustrate Reich’s “Jewish” music (though he also continues to compose other forms). Read on.

Above: Photo of Steve Reich famously wearing a kippah under his baseball hat. Stevereich.com.

Tehillim (1981)

Reich wrote Tehillim (the Hebrew word for Psalms), based on sections of four Psalms, in Hebrew, with voices and an ensemble including winds, percussion, strings, and organs. It is a revelation and celebratory, and when I first heard it back then, I couldn’t stop listening. Before writing it, Reich traveled to the Middle East, recording traditional Hebrew cantillation from diverse sources, and published an essay in French and Italian; it was published in English in 1982 as “Hebrew Cantillation As An Influence On Composition”. The piece uses the pulsing, canonic format of his other works, with the rhythm of the music coming directly from the rhythm of the Hebrew text. He even utilizes the meaning of the text for musical shape: when the singers sing in Hebrew the phrase “Turn from evil…” the melodic line goes down; when they sing “…and do good,” it rises. The word tov (good) ends on a strong major triad; the word ee-kaysh (perverse), on a dissonant minor chord.

Above: (6 min) Tehillim: IV. Psalm 150:4-6, “Halleluhu batof umachol” · Alarm Will Sound. Steve Reich: Tehillim / The Desert Music. ℗ 2011 Cantaloupe Music. Released on: 2011-01-01. Conductor: Alan Pierson. Ensemble: Alarm Will Sound. Orchestra: Ossia. Composer: Steve Reich.

Different Trains (1988)

Following more successes, Reich composed this groundbreaking composition for the well-known string quartet Kronos. As he described it, “Different Trains for strings and tape has its roots in my early taped speeches It’s Gonna’ Rain and Come Out.” Drawing on his childhood rail travel, Reich wrote “I now look back and think that, if I had been in Europe during this period, as a Jew I would have had to ride on very different trains.” He uses recordings of the voice of his governess Virginia, the voice of a retired train porter who traveled the same routes he rode, collected recordings from three Holocaust survivors living in the US who were the same age as he back then, and train sounds from the US and Europe. The piece uses fragments of the recordings as musical motifs, with the strings imitating taped speech melodies and train sounds (some performances add visuals). The three sections: 1. America – before the war, 2. Europe – during the war, and 3. America – after the war, are a powerful and engaging testament to the Holocaust.

Above: (12 min) Excerpts from Different Trains performed by ConTempo Quartet in Belgium 2020, with visuals by Mihai Cucu.

Traveler’s Prayer (2020)

Of his latest piece, written before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, Reich writes, “The virus shifted the gravity of the words I was setting which were three short excerpts from Genesis, Exodus, and Psalms. These excerpts are usually added to the full Traveler’s Prayer found in Hebrew prayer books.” A slower, less upbeat composition than many of his others, it is a meditation on the fragility of life, on hope, and on mortality. Two of the texts are also used in Reich’s previous piece written in response to the World Trade Center terrorist attacks, WTC 9/11.

Above: (2 min) The Colin Currie Group with Synergy Vocals, conducted by Colin Currie. Recorded live for NPO Radio 4 at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam 2021.

Reich Traveler’s Prayer Translation/Transliteration:

Behold, I send a messenger before you to protect you on the way and to bring you to the place that I have prepared. (Exodus 23:20)

hin·nêh ’ā·nō·ḵî šō·lê·aḥ mal·’āḵ lə·p̄ā·ne·ḵā, liš·mā·rə·ḵā bad·dā·reḵ; wə·la·hă·ḇî·’ă·ḵā, ’el- ham·mā·qō·wm ’ă·šer hă·ḵi·nō·ṯî.

הִנֵּ֨ה אָֽנֹכִ֜י שֹׁלֵ֤חַ מַלְאָךְ֙ לְפָנֶ֔יךָ לִשְׁמָרְךָ֖ בַּדָּ֑רֶךְ

וְלַֽהֲבִ֣יאֲךָ֔ אֶל־הַמָּק֖וֹם אֲשֶׁ֥ר הֲכִנֹֽתִ:

To Your lifeline I cling, Eternal, I cling Eternal, to Your lifeline, Eternal, to Your lifeline I cling.

(Genesis 49:18)

lî·šū·‘ā·ṯə·ḵā qiw·wî·ṯî Yah·weh.

לִֽישׁוּעָתְךָ֖ קִוִּ֥יתִי יְהוָֽה

The Eternal will guard your departure and your arrival from now till the end of time (Psalm 121)

Yah·weh yiš·mār- ṣê·ṯə·ḵā ū·ḇō·w·’e·ḵā; mê·‘at·tāh, wə·‘aḏ- ‘ō·w·lām.

יְֽהוָ֗ה יִשְׁמָר־ צֵאתְךָ֥ וּבוֹאֶ֑ךָ מֵֽ֝עַתָּ֗ה וְעַד־ עוֹלָֽם

EXTRA: Steve Reich on Traveler’s Prayer

“The score is a marked departure for Reich, notably devoid of Reich’s signature driving pulse, and instead featuring free-floating vocal lines that circle each other through retrograde and inversion.” For an extra treat, watch this video from Boosy & Hawkes (4 min, above) in which Steve Reich discusses composing Traveler’s Prayer.

Other pieces of Reich’s music with Jewish content include The Cave (1993), a multimedia/opera for musicians, singers, and video co-created with his wife, videographer Beryl Korot; which explores the connections between Jews, Palestinians, and Christians to the sacred tomb of Abraham, Sarah, and their families in Hebron on the West Bank, and the Daniel Variations, which combines text from Daniel Pearl, the Washington Post reporter murdered by Islamic fundamentalists in 2002, and the prophetic book of Daniel in the Bible.

Reich music is not easy. It’s complex and rich, it demands attention and defies traditional categories yet pays homage to them. But his impact is profound, and his Judaism is deep. Listen. Watch.

Jim Ball is the PR Manager and a founding member of the Jewish Arts Collaborative (JArts). He has had a long career in public relations in the Boston area, working for the Harvard University News Office, Massachusetts State Government, private agencies, and organizations, and served as Press Secretary for the MBTA. A freelance journalist early in his career, he wrote for the Boston Phoenix, the Somerville Times, and the Cambridge Tab. His most recent writings are available on JewishBoston.org. Jim was the co-founder with Joey Baron of the Boston Jewish Music Festival, which merged with the New Center to become JArts. A longtime musician, Jim now sings with the Newton Community Chorus.

Jim Ball is the PR Manager and a founding member of the Jewish Arts Collaborative (JArts). A freelance journalist early in his career, he wrote for the Boston Phoenix, the Somerville Times, and the Cambridge Tab.

Reflections

Reich’s Different Trains (and some of his other pieces) use human voice recordings as melodic material, taking snippets of phrases as motifs. Can you hear how he does this? Does speech have melody? What else can you hear that Reich uses in this piece for musical elements?

In Tehillim and Traveler’s Prayer, Reich uses Hebrew text rather than English. Does the Hebrew influence the music? How? What elements do you hear that are common in both pieces—and what are some differences?

"The Traveler’s Prayer" is traditionally said as one begins traveling. Reich says he says the prayer before he flies in a plane. Compared to many of Reich’s other pieces, the pulse and tempo of this piece are slower and more subdued. What else might he be trying to communicate here?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox