Spirit Possession in Judaism: A brief introduction to the dybbuk, ibbur, and zogerkes

Published Jan 3, 2023

Spirit Possession in Judaism

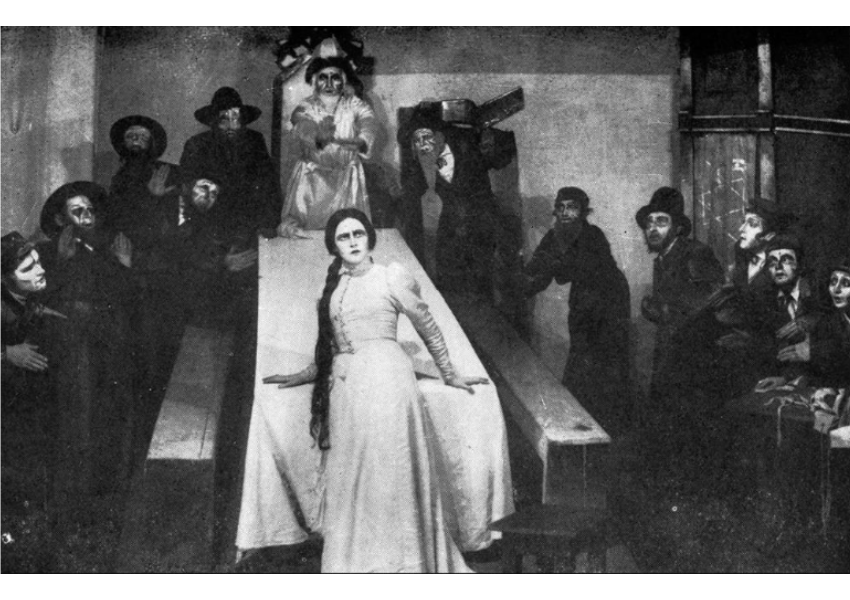

Above: The possessed heroine of the Yiddish play The Dybbuk from a 1922 production (YIVO Archive)

Judaism, in its now familiar American form, does not foreground ghosts or spirit possession as a high-profile part of its public image. And yet, the high value placed on memory and practices of memorialization in Jewish life belie the assertion that Judaism is exclusively focused only on the living. While an overriding ethos of rationalism plays a controlling role in much of contemporary American Judaism, Jewish tradition includes a vibrant set of teachings and practices associated with consort with the dead and focused on the intermingling of spirit and living worlds.

In this brief article, I will touch on three main areas in which themes of spirit possession emerge in Jewish tradition: intimate possessions, in which spirits enter the body of an individual, protective practices that intentionally cultivate relationships with the dead to protect the living, and rabbinic spirit practices that highlight the role of belief in the spirit world as a constitutive element in the world view of the leaders of “normative” Judaism.

The most famous story of ghost possession is told in S. Ansky’s 1918 Yiddish play, The Dybbuk. The play tells an oft repeated story of young lovers torn apart in life and reunited in death. Ansky’s story innovated the introduction of a love narrative into the story of a dybbuk, a form of intimate spirit possession that would have been familiar to his Yiddish-speaking audience at the time. The term dybbuk derives from the Hebrew word לִדבּוֹק (cleaving), and describes the intrusion of a ghost into a living body, often a male spirit entering a woman. A dybbuk possession is intrinsically non-consensual and is typically followed by an exorcism, presided over by rabbis. Scholar of Kabbalah, J.H. Chajes, has suggested that dybbuk possession at times served a secret function as a means of giving women access to a public forum for forbidden speech and self-assertion, under the guise of uncontrollable manifestations of their possession.

Another form of intimate possession involves the intentional invitation of a ghost into a living body. An ibbur, a term derived from the Hebrew word לְעַבֵּר (impregnation), was an act of veneration of an ancestor or revered figure from the past whose strength was called upon to address a specific practical or spiritual need. Ibbur spirit invitation reflects the generally positive appraisal the Jewish tradition takes of the world of the ancestors, in comparison to a presumedly more spiritually impoverished present.

Jewish protective spirit practices reflect this spirit of ancestor reverence. The recent translation into English of the ethnographic report on S. Ansky’s ethnographic mission to the Russian Pale of Settlement and the exciting research of scholar and kohenet Annie Cohen have highlighted the role of women’s spiritual lives and magical practices in the Yiddish speaking Jewish world. Zogerkes, or zogerins, were women spiritual practitioners whose remit included both serving as prayer leaders in the women’s section of synagogue and working in cemeteries. In the cemetery, zogerkes worked as intermediaries communicating with the souls of the dead, often to petition on behalf of their still living family members. The graveyard emerges in these narratives as a site of community, where the living and dead were interdependent and in direct communication. Intimacy with the dead extends outside of the cemetery into the synagogue and the home through Jewish practices such as saying kaddish (the mourner’s prayer), or lighting yortsayt (death anniversary) candles.

In the realm of prestigious rabbis and textual tradition, ghosts also play a role. The ibbur, discussed above, was a highly regarded practice among Kabbalists. The moment of death is considered a key point in the life of a Torah scholar, and by being present at this death, disciples of a great rabbi can achieve an influx of holiness and power. The pioneering sixteenth century Kabbalist Rabbi Isaac Luria developed a system of spirit lineages and could tell his students which spirits of ancient sages and Biblical figures were present in their souls. Spirit lineage reading was figured as a healing practice that could diagnose physical and spiritual ailments.

All of the practices touched upon in this brief summary connect to the overarching theme of the productive role of ancestors in the lives of the Jews. While ghosts can at times present danger to the living, the main function of the spirit world in the Jewish tradition is as a protective force. Practices of memorialization and even specific invitations of the dead into the space of the living are productive forms of contact between worlds that create opportunities for comfort and strength to be given to the living.

Jeremiah Lockwood is a scholar and musician, working in the fields of Jewish studies, performance studies, and ethnomusicology.

Reflections

Memorial practices in your life

What role do memories of ancestors play in your life? Do you have practices that keep spirits close to you?

Ghost Stories

Have you ever seen a ghost? Have you ever dreamed about a departed intimate?

Communication with the Other World

If your most beloved intimate who has passed into the other world could speak to you, what do you imagine they would tell you?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox