A Debut Novel Merges the Worlds of Hasidism and Pornography: Interview with Felicia Berliner

Published Dec 28, 2022

A Debut Novel Merges the Worlds of Hasidism and Pornography

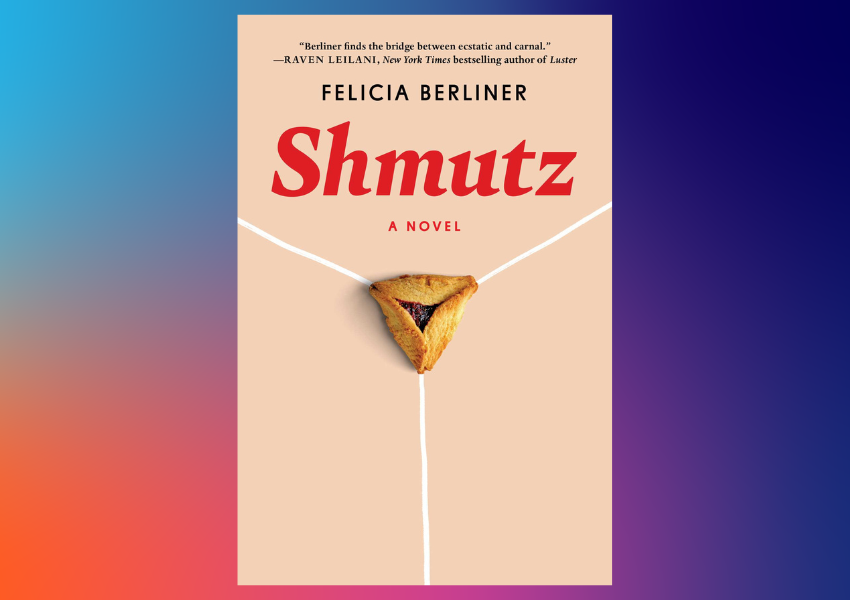

Shmutz: A Novel adds another layer to the meaning of the Yiddish word for dirt. This fiction debut takes its place among recent books that have cracked open the cloistered world of the Hasidim. The contemporary subgenre includes Pearl Abraham’s novel The Romance Reader, Deborah Feldman’s memoir Unorthodox: The Scandalous Rejection of My Hasidic Roots which was the basis of a Netflix series, and now the powerful Shmutz by the pseudonymous Felicia Berliner.

Berliner introduces readers to 18-year-old Raizl, whose Hasidic family has reluctantly allowed her to attend a local college on a scholarship and study accounting. It’s a highly unusual opportunity for a Hasidic girl and comes with a laptop. The laptop is Pandora’s box among Hasidim, who shun television, the Internet, and any other conduit that accesses the outside world. As a result, Raizl is under strict orders to use her new computer only for schoolwork.

Late one night, the bright and curious Raizl opens the box of woes at her fingertips and Googles “God” and “kiss”. The search terms bring an onslaught of pornographic images and videos that frighten and then intrigue her. She watches it all under the covers while her younger sister sleeps a few feet away.

Rather than depicting the laptop as an instrument of the devil, Berliner presents Raizl burning a different sort of “midnight oil”, illuminating her complicated journey of self-discovery. Pornography is both troubling and exciting to Raizl. For a young woman destined to have an arranged marriage, none of the sheltered Yeshiva boys with whom she is paired are appealing. The more pornography she watches, the dimmer her marital prospects seem.

The mashup of languages inside Raizl further clarifies her psyche. This mashup, or Raizlish as Berliner calls the stew of language that emerges, is a striking example of translanguaging. In her new circumstances, Raizl has absorbed a more sophisticated English, a modern version of Yiddish, and a new lexicon of pornography. This mixing of languages are an effective inciting incident, offering Raizl a novel vocabulary to connect her sexual identity to her Jewish soul.

Felicia Berliner talked with Kolture about experiencing new worlds along with Raizl as she wrote Shmutz, and that provocative hamantasch on the book jacket.

Kolture: What moved you to become a writer?

Felicia Berliner: Listening to the narratives in the Torah had a big impact on me as a child. The idea that stories are part of the universe’ creative force is how I think about writing and storytelling.

K: Why do you write under a pseudonym?

FB: There is a long literary tradition of pen names, especially for women writers. In today’s media environment, there’s even more reason, especially for women writing with sexual content, to want other parts of their lives separate from their work. The most important thing is having a voice, and the pen name is a strong voice for me. It was part of the process that gave me permission to write the book.

K: Why is there a hamantasch on the book’s cover?

FB: Hamantaschen is a traditional Jewish Purim pastry. But it also has a shape that can be reminiscent of a vulva; it brings together sexual and Jewish identity, which is at the novel’s core. For Raizl, Jewish and sexual identity are completely intertwined. They can’t be separated, and the cover of the book conveys that message.

K: What did you want to convey through Raizl multiple identities?

FB: The Maggie Nelson epigraph in Shmutz says, “It’s the binary of normative/transgressive that’s unsustainable, along with the demand that anyone live a life that’s all one thing.” I wrote the book to discuss what’s possible and how we can better accept that people of any age – certainly 18 or 19-year-olds – don’t have to choose between their sexual identity, their families, and their faith.

K: Why did you set the book in a Hasidic community?

FB: I set Shmutz in an ultra-orthodox family because otherwise it’s very rare to find anybody who is completely sheltered from online pornography and sex. And choosing Raizl as the book’s protagonist allowed me to show the full force and shock of online porn, something central to the story.

K: Your book presents a mashup of Hebrew, English, and Yiddish. I’ve heard you describe this mashup as “translanguaging.” What does the term mean?

FB: Any Yiddish speaker is translanguaging. Yiddish pulls from many sources, and Shmutz has at least those three languages you mentioned. Raizl’s also makes up a language that is her version translanguaging. I call it “Raizlish.” The binaries of normative and transgressive the book push against also apply to language. Raizl is challenging the hierarchy of language. Even the language spoken in her college classroom is hierarchical compared to the language of porn.

K: What in your background served you when writing Shmutz?

FB: As I was writing, I was grateful for my Orthodox Yeshiva education. I’m deeply connected to Orthodox ritual life and culture through friends and family. I also have my own practice in which I don’t fit into neat boxes or categories.

K: How did you research Shmutz?

FB: Raizl is discovering language online, so anything that I, as a writer, found online was something that Raizl, an intelligent young woman, found by what I call “shmugoogling.” Her research was my research.

K: What was revelatory for you in writing Shmutz?

FB: The process of learning and exploring language as a newcomer to the sexual territory online. That process was a joy and an opportunity for me to grow.

K: What challenged you?

FB: I was clear from the beginning that Raizl’s dilemma is the seed and core of the book. Writing about that dilemma was joyous and what propels the book forward. There are no tidy conclusions. A book that ties everything up at the end too neatly would not be true to life. And it certainly would not be true to Raizl’s life.

K: What do you hope readers will take away from Shmutz?

FB: Many of us have multiple identities, and it can be painful to be pressured to be one thing. My message is to be all the parts of yourself – your linguistic identities, as well as your faith, gender, and sexual identities. All those identities are vital.

Click here to find Shmutz: A Novel at your local library.

Click here to buy Shmutz: A Novel.

Judy Bolton-Fasman is the author of ASYLUM: A Memoir of Family Secrets from Mandel Vilar Press.

Reflections

Addiction vs. Attraction

Raizl says she's addicted to pornography – (After you read the book: Is she addicted or attracted to it?) What are the differences between addiction and attraction

Community

What do you find fascinating about faith-based community (like Hasidim)?

Translanguaging

What are examples of "translanguaging" in your life?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox