Tu BiShvat Poster | Steve Marcus Poster Series

Published Jan 27, 2023

Tu BiShvat Poster

Tu BiShvat, ט״ו בִּשְׁבָט, literally means the “15th (day) of (the Hebrew month of) Shavat”. The “Tu” stands for the Hebrew Letters, Tet and Vav, which together have the numerical value of 9 and 6, adding up to 15, which is the day of the observance. The holiday is also called Rosh Hashanah La’Ilanot, ראש השנה לאילנות, which translates to “New Year of the Trees”, as stated in the first Mishna of the first chapter of the Mishna Rosh Hashana.

In contemporary Israel, the day is celebrated as an ecological awareness day, like Earth Day, and trees are planted in celebration. The Jewish National Fund’s famous “plant a tree in Israel Campaign” is inspired and connected to this day. Besides planting trees in honor of others in the Holy Land, people also host small seders, which include fresh and dried fruits and nuts so they may say blessings over the fruit of the trees.

Be strong and we will strengthen one another.

— Reb Simcha Yosef ben Yehuda Ha’Levi

AKA Steve Marcus, Artist

Tu BiShvat Poster (close up 1)

Tu BiShvat Poster (close up 2)

About the Poster Series

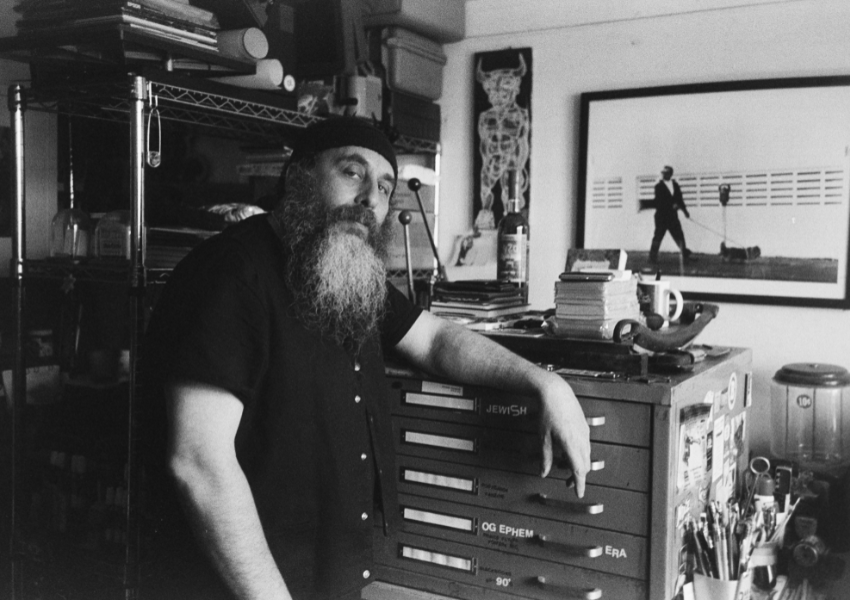

NYC Artist, Steve Marcus writes about his new series for the Jewish Arts Collaborative:

“There’s an old saying that a skilled laborer works with their hands, a craftsman with their hands and mind, but an artist works with their hands, mind, and heart. This trinity of the hands, mind, and heart is accessible for artistic manifestation by any human being, regardless of race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, or gender. Within the mind-boggling diversity of the human population and its countless artists— now capable of tracing their ancestors’ origins to every corner of the globe— one may wonder, what makes art “ethnic”?

Ethnic art incorporates and expresses a specific people’s culture, history, and collective experience. When artisans and their work are both descended from a specific group’s said collective experience, and the artisan chooses to wrestle with the inner torment of the group’s reality with the hope of communicating the subtleties of their unique daily experience and thought processes, the subject of the work becomes the artisans themselves. The work can then be considered authentic “ethnic art”. However, not all art crafted by the hands of ethnic artisans can be classified as ethnic art. When craftspersons of distinct ethnicities create objects without ethnic content, the “ethnic” adjective refers to the artist and not the art. And if an artisan creates art that has ethnic content relating to an ethnicity that is not their own, then the ethnic adjective refers to the art and not the artisan. In this case, the artisan may be knowledgeable of the subject matter, so the art may mimic ethnicity, but it will not be informed by an authentic experience. The exploitation of that inner experience by someone from a separate culture amounts to “cultural appropriation”.

In the era of globalization, the ugliness of cultural appropriation has become rampant, as various “outside cultures” are now easily accessible with the assistance of the internet and social media. The digital-age specter of colonialism, imperialism and social Darwinism disseminates information and imagery at a dystopian pace. Consumers hijack distant cultures’ attitudes and style cues to mold themselves into the hipster approximations of cultures they have never experienced firsthand. This form of imitation is the stylistic manifestation of colonial imperialism and is helping to pave a bland and blind path toward a global monoculture.

Many descendants of the founders of monotheism are suckers for the global monoculture—no longer a nation within a nation, they are being absorbed into the matrix. The greatest existential threat to the Jewish people is the Jewish people themselves. The apologetic and sometimes dismissive attitude Jews have about being Jewish, to the point of assimilation, has left most Jewish artists and institutions struggling through a postmodern identity crisis. They’ve abandoned so much of their own intrinsic identity, creating art that begs for acceptance from their own tormentors. This current series of work for the Jewish Arts Collaborative expresses my own roots and culture by creating images for the annual festivals, holidays, and observances of the Jewish calendar, which proudly contain Jewish values as a celebration of authenticity. However, the artwork is not just a creative declaration of my own identity and beliefs but also created to inspire all people to celebrate and explore their own true identities in a creative rebellion that smashes falsehood and hatred. The quest for the truth will lead to oneness. Be strong and may we be strengthened.”

Steve Marcus (aka smarcus) has received honors and awards from the American Society of Illustrators and has several works in the art and American history collections in esteemed institutions, notably the Oakland Museum of California, The Jewish Museum of Florida – FIU, The Yiddish Book Center, The Harvard Library, Yivo Institute for Jewish Research and The Miami-Dade PLS. He is acknowledged as one of the Lower East Side’s most culturally influential residents in, “Jews: The People’s History of the Lower East Side” and his work is written about by professors from Ohio State University, Tulane University, Florida State University, Harvard University and in scholarly books published by Duke University Press, The University of Texas Press and the Florida International University. Steve is a member of the American Guild of Judaic Art.

This work was commissioned by the Jewish Arts Collaborative in 2022. Stay tuned for more posters in this series.

Other posters in this series: Hanukkah, Purim, Passover. Stay tuned for more.

(Above: Photo by Ziggy York)

JArts’ mission is to curate, celebrate, and build community around the diverse world of Jewish arts, culture, and creative expression. Our vision is of a more connected, engaged, and tolerant world inspired by Jewish arts and culture.

Reflections

Connect with your roots

Trees are a recurring theme/symbol in Jewish religion and culture. What other holidays, events, or symbols can you think of in Jewish life that involve trees?

Assimilation

One of the central ideas of this series is a grappling with assimilation and the abandonment of identity. How does the artist’s work embody authenticity and “creative rebellion”?

“Ethnic art”

What do you think makes a piece of art “ethnic”? How do you define “Jewish art”?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox