Come Inside: The Sukkah of Peace (Part 1/5)

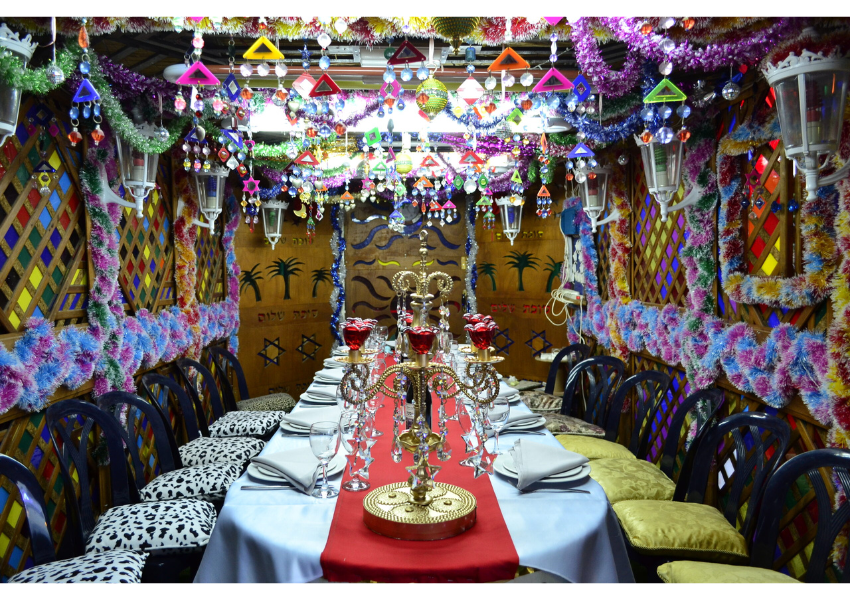

Welcome to the inspired ritual shelter—or sukkah—that Shaul Moyal designed and built by hand for over 40 years in observance of the annual Jewish festival of Sukkot.

“I had the dream to make this sukkah from the age of ten,” he said in 2010. “We used to make a sukkah in Morocco out of reeds and sticks and once we finished building it and sat down to eat, the wind would blow and knock it down. It was then that I said, ‘That’s not enough! It should be strong.’”

(Click the next slide to continue on.)

The Sukkah of Peace (Part 2/5)

Shaul was born in Marrakesh in 1938 and grew up in an area of the city that he described as a “fortress” or “camp,” an area surrounded by a wall that enclosed the Jewish shops and homes with an entrance gate guarded by a Muslim Moroccan official—this was the mellah. He emigrated with his family to Israel in 1956 and lived in a transit camp for Iraqi and Moroccan immigrants before settling in Jaffa. Shaul worked in fruit orchards, enlisted in the military, and taught himself electrical mechanics while working in construction.

Reflecting upon his lifetime of movement and labor, Shaul said, “Oh! What I’ve gone through in my life! I’ve had enough.”

The Sukkah of Peace (Part 3/5)

When the first of his three daughters were born, Shaul began building his sukkah, building tradition, fortifying it, and decorating it further each year to reflect his dreams of stability, home, and hope.

The socio-economic struggles that Shaul experienced throughout his life stand in stark contrast to the promise and potential that he brings to his sukkah construction. I was lucky to meet Shaul while carrying out 16 months of ethnographic fieldwork on the construction, decoration, and interpretation of contemporary sukkot, the temporary ritual shelters that observers of Sukkot annually build. My research was centered in Shchunat Hatikva, a working-class, multi-ethnic neighborhood of South Tel Aviv, Israel, but it extended into neighboring communities, like Shaul’s, where I studied the purpose and variety of this Jewish ritual in areas struggling with social and economic disadvantage.

The Sukkah of Peace (Part 4/5)

Each year, Shaul spent over five weeks hand-building his sukkah—assembling hand-carved walls, a custom oblong table, black-and-white checkered seats and flooring, bejeweled chandeliers, and multitudes of lights. He installed a landline phone on one wall that he wired to the neighborhood telephone pole, as well as an intercom to dial up directly to his fourth-floor walk-up apartment. When I asked Shaul what he thinks about when he sits inside his sukkah, he responded, “I try to think about how I can make it better next year, for there is no end to beauty.”

Shaul’s sukkah is a place of creativity, a place to dream of the future in spite of the past, and a place of hope.

The Sukkah of Peace (Part 5/5)

His daughter Sivan, partner in his sukkah construction and photographer (of these images and more), said of her father’s sukkah observance, “Perhaps it was the hard life he lived, maybe the ups and downs of the economy, or of the emotions, but the portability of the sukkah meant, ‘Do not despair, do not lose hope. It was destroyed? Build it again.’”

By transforming a lifetime of uncertainty, uprootedness, and struggle into an annual expression of determination, home-building, and dreaming, Shaul and Sivan remind us how the ancient observance of Sukkot reflects the eternal need for housing, longing for home, and will to create.

Gabrielle A. Berlinger is an Assistant Professor of American Studies and Jewish History and Culture at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Reflections

Reflect

What makes you feel “at home” (physically, socially, culturally)? How do those feelings of being “at home” give you a sense of belonging, and belonging to what (a people, a place, a time…)?

Get creative

How would you design and construct a temporary structure symbolic of the home? What materials would you use to build and decorate, and what might they convey about your history, your present conditions and your dreams of the future?

Observe

Can you imagine how an ancient religious ritual can reveal contemporary social, cultural, and political values?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox