Eruv and Its Materials: Boundaries in the Jewish Community

Artist Suzanne Silver talks the symbolism of the Eruv and her installation exploring it

Published Mar 17, 2023

In conversation with artist Yevgeny Fiks, Suzanne Silver reflects on her installation, “Kafka in Space” which is an exploration of the eruv, the symbolic wire boundary of the Jewish community.

Yevgeniy Fiks: For our readers who might not be familiar with the term, what’s an Eruv?

Suzanne Silver: The eruv is a symbolic boundary made with wire or string that is suspended along vertical posts to circumscribe an area in a community. It has been described as a fishing line above the skyline and it allows observant Jews to perform certain activities like carrying or pushing objects without violating Sabbath law. It extends the private domain of the home to the public domain. The eruv appears in the architectural tractates of the Talmud. It can be thought of as legal fiction.

Fiks: What is the connection between the Eruv and Franz Kafka?

Silver: I was introduced to a quote from Kafka’s Aphorisms in which the institution of religion is the likely focus of his remarks. The “rope” to which he refers may be the material used with wire, string, walls, and poles to demarcate space in a functioning Eruv.

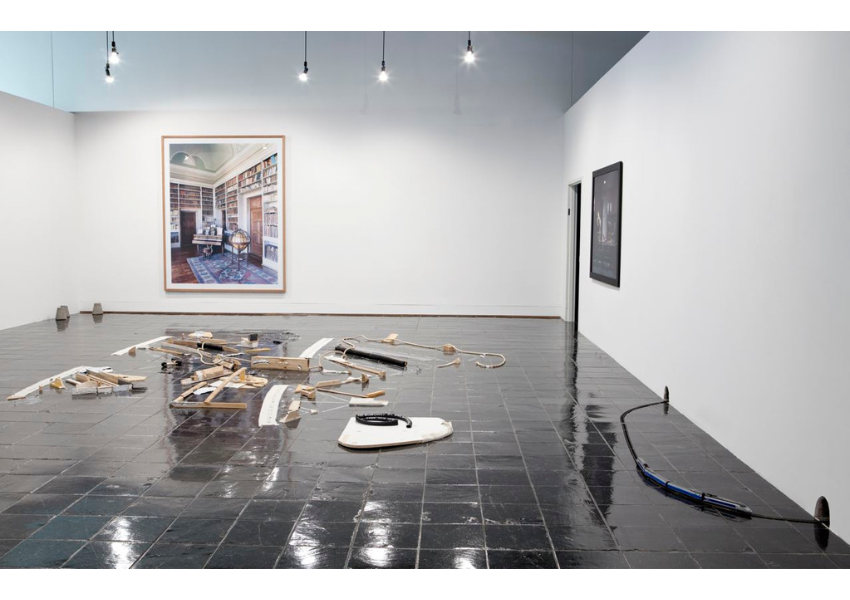

Fiks: In your installation “Kafka in Space (Parsing the Eruv)”, you created a visual diagram of a quotation by Kafka: “The true path leads across a rope that is not suspended on high, but close to the ground. It seems more intended to make people stumble than to be walked upon.” Why did you pick this particular quotation and what strategies did you use to visualize it?

Silver: Kafka’s observation coincides with my own suspicions about the Eruv, as I think what happens on the ground, i.e., on earth, is what is important. It echoes my own doubts about the role of religion and its perils. I visualized it as a sentence diagram composed of building materials. I have been using the sentence diagram in my work as a structure which I then subvert. Traditionally, a sentence diagram dissects grammar, but if you don’t know how to read it properly, the word order might change and a type of found poetry is created. It, therefore, combines rational and irrational elements.

Fiks: The installation is composed of building materials, including wood, vinyl, rope, rubber, muslin, wood glue, wire, chalk, pigment, and neon. What’s the significance of these materials for the artwork?

Silver: These are the materials of construction – of building a home, and by extension, of building a language. As separate pieces, they are ways of deconstructing a building or a language and symbolically deconstructing meaning.

My suspended Eruv sign is made of white neon. A neon sign is more likely to be found advertising beer and cigarettes or a sex shop than in a religious context. The white glow of the Eruv sign is a noncommercial illumination. The illuminated Eruv represents the idea of an inscribed space and functions literally to announce Eruv in both Hebrew and English. In the (“Of Other Spaces”) installation, the neon sign is suspended in the rafters high above the diagram of the parsed sentences from Kafka in a dialectical relationship between ritual, religion, language, and the inscribed and prescribed parameters of human behavior.

Fiks: Can you please talk about your idea of transformation of the public to private and the secular to sacred in the context of this artwork?

Silver: Through the legal fiction of the Eruv, public space becomes redefined within its boundaries and becomes the private space of a specific community. Put another way, the private space of the home is extended to the public domain as long as it exists within the parameters of the Eruv.

I am interested in notions of the transformation of the public to private and secular to sacred in the context of my personal art and as it relates to my Eruv project. I often pursue lines as cartographic and conceptual boundaries and have now introduced lines as Eruv, which allows for the conceptual transformation of space.

Fiks: How is language used in this artwork?

Silver: I make drawings, objects, and installations where unexpected materials are combined to explore the disorder and evasiveness of language. I pay homage to the vernacular of signs (theatre marquees, carnival displays, picket signs, shop signs, inscriptions, and incantations) to create a visual language that is open to multiple readings.

In the floor component of the installation, Kafka’s sentences are parsed in the form of a “tree diagram”, the system of grammatical analysis favored by contemporary linguists. The syntax of the sentence can be diagrammed according to the rules, but its significance is more elusive. Is it meaningless or a profound arrangement of thoughts, depending on the order in which it is read? I tried to capture this combination of rational and irrational, poetic and absurd.

I have continued to explore the parsing of quotations from Kafka, Proust, and Ferlinghetti as well as my own sentences, in which the words are given physical form using construction materials and light. Throughout, associations float or weave in and out as meaning is determined by piecing together the visual clues.

Yevgeniy Fiks is a Moscow-born New York-based artist, author, and organizer of art exhibitions.

Reflections

For anyone:

What do you know about the relationship between physical space and language in the Jewish tradition?

For museum-goers:

Do you know any other artists who address the Eruv in their art?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox