How To Talk To Your Kids About Antisemitism

Illustrator Paul O. Zelinsky discusses two books that make discussing antisemitism with children more approachable

Published Sep 27, 2022

Parents of young children get questions about everything from “if a fly has wings, is it a bird?” to “where do babies come from?” and often reach for a picture book to help give answers. But for Jewish parents, books on antisemitism for kids are hard to find, and, at a slightly older age, finding a non-traumatizing way to talk about the Holocaust is even harder.

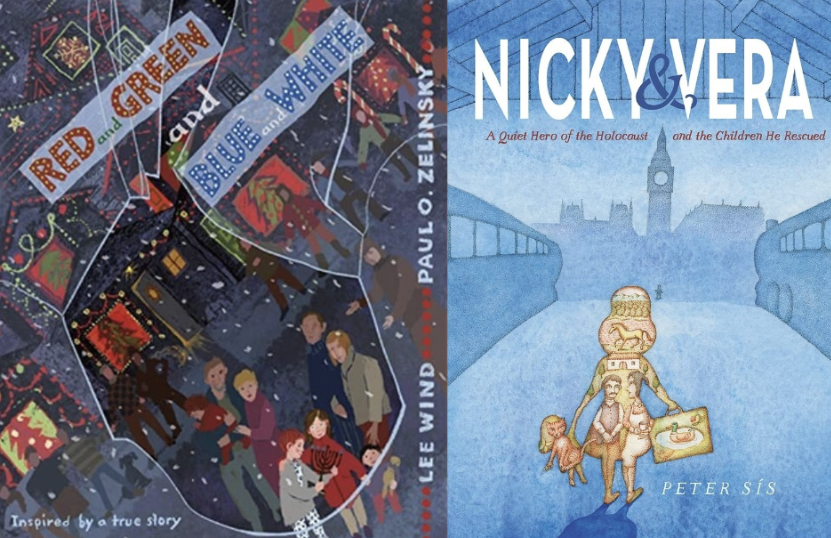

Two recent picture books are spot on for opening these conversations in honest, thoughtful, yet hopeful ways. Red and Green and Blue and White by Lee Wind and illustrated by Paul O. Zelinskyan adaptation of a true story: after an antisemitic incident in the U.S. where Isaac’s family’s window is broken, one courageous child, Isaac’s friend Teresa, leads the community to stand behind Isaac and his family.

The second book, Nicky & Vera, written and illustrated by Peter Sís, tells the story of Nicholas Winton, an unassuming hero who rescued Jewish children from Prague, putting an emphasis on what each and every life means, and all that each life entails. Both books use real stories and rooted truths to tell stories children can understand and internalize, accepting both the pain and the hope these creators offer.

Q&A with Red and Green and Blue and White Illustrator Paul O. Zelinsky

Deborah Furchtgott: Did experiences discussing antisemitism with your children return to you as you worked on this book? Did you have conversations with your own parents about it?

Paul O. Zelinsky: My family has been very lucky, all things considered. None of my family was lost in the Holocaust. They’d all already reached the USA or were in Russia out of range of the war. My father’s father escaped Russia to avoid conscription into the Tsar’s army for WWI, because, he said, as a Jew he stood very little chance of coming out of the army alive.

In my family, the topic of antisemitism came up, but not really in the charged way that you’re talking about, as far as I recall. When and where I grew up was one of the more golden ages of Jewish existence in the larger world, and I try to appreciate that fully. I have to admit to not having had that a talk like that with my young daughters. They were plenty old enough when they eventually learned about it. But the feeling of fear, and of imagining unknown forces that don’t have your interest at heart— that’s not unique to antisemitism, and certainly not unknown to me.

One of the main things I liked about Lee’s manuscript was that it approaches antisemitism in such an implicit way. Or maybe it would be truer to say that Lee chose a story to tell that happened not to involve the more brutal aspect of the phenomenon — actual people expressing antisemitic thoughts and ideas.

Furchtgott: The thrown rock at the climax of the Red and Green and Blue and White trailer evokes Kristallnacht to an adult reader, though not a child. Did that comparison occur to you as you worked?

Zelinsky: Yes, certainly I thought about Kristallnacht. But I don’t think that thought is necessary to understand the story. When it comes to looking at a picture, I’m not sure what the difference is between an adult’s and a child’s perspective. Nothing here is a specific visual reference to Kristallnacht. If I could have done that, I wouldn’t have. Mostly I wanted to make the thrower as indistinct as possible. As in the text, the focus is on the event. The quality of the line is rough and almost violent. I showed my unfinished art to a friend who thought the gloved hand looked not like a hand, but like a bear. I had to work the bear out of it, and sometimes I still see it there.

Furchtgott: Maurice Sendak (Where the Wild Things Are) was among your teachers. Did his teaching come back to you as you worked?

Zelinsky: Yes, I think about Maurice quite a lot, not just in this context. The idea that even the smallest of children are no strangers to depths of terror— that didn’t originate with him, but he certainly held to it. He forcefully rejected the notion that children’s books should never stir up those feelings, and I’m with him on that. Would you like to read only books that don’t stir up strong emotions? People can feel deeply rewarded by stories that take them to dark places and then back.

Furchtgott: This is a book of pain and hope and communal response. How do you balance the emotions in your art?

Zelinsky: I think it’s a book far more of hope than of pain. If there were no pain in it, the hope wouldn’t have meaning. The greatest thing about the story is that (even though there was some fictionalizing in the text) it really happened.

I was able to approach my illustrations in the same way I do generally, by immersing myself in the emotions of the story and trying to figure out how they could be expressed with shapes and colors, body language, and expressions. We do see Isaac being afraid, huddling on the floor not far from the broken window, a police car outside, and police inside having grown-up conversations. I just drew what it felt like to me when I read and read and read the story, trying to inhabit it.

There’s an inescapable tendency to make any story symbolize more than itself. Red and Green and Blue and White (as I see it) isn’t claiming that the world got better after this happened. But it is saying that people can be good, because they were, and that’s something to remember these days. The great climax [is] where Isaac’s poem is the featured topic, highlighting what Lee really wanted to get across “stronger together, shining bright.” I did, though, take the opportunity to draw that whole city with the menorahs and the Christmas lights in deep blue night.

Find Red and Green and Blue and White or Nicky & Vera at your local library.

Find Red and Green and Blue and White or Nicky & Vera at bookshop.org.

Deborah Furchtgott is a children's book reviewer at The Children's Bookroom.

Reflections

For grown-ups:

Do you remember how you learned about antisemitism? Would books like these have helped? Why or why not?

For bookworms:

These books both ultimately focus on courage, hope, and individual action. What was the last book you read, as an adult, that took that focus? How do you balance fear and hope in your reading?

Art and feeling

In his interview, Paul O. Zelinsky talks about representing fear, but also hope and precipitating himself into the emotions to get the art right. His art is uniformly beautiful. How do you feel about complicated emotions being shown beautifully? Should fear look beautiful?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox