Tikkun Ha-Olam, Finding Home

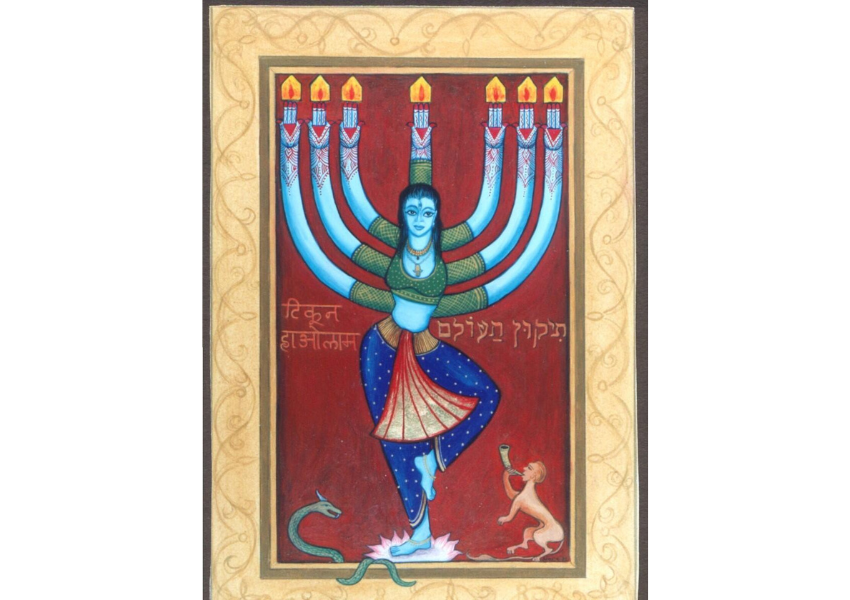

Above: Tikkun Ha-Olam, Finding Home Series #46 (2000) by Siona Benjamin. Collection of Jonathan and Gail Schorsch. Courtesy of the artist.

Siona Benjamin grew up Jewish in Mumbai, India, her friends mainly Hindu and Muslim, attending Catholic and Zoroastrian schools. She came to study art in the American Midwest and now lives in New Jersey.

Her art reflects her diversity: the tradition of Indian and Pakistani (particularly Mughal) miniature painting, Persian miniatures and 18th-century Rajput—Northern Indian—art. Hindu-based figures against geometric, vegetal and floral patterns reflecting Muslim art. Gold leaf, non-perspectival backgrounds recalling Byzantine icons, medieval Christian paintings—and illuminated Christian and Jewish manuscripts. She is inspired by the bold Bollywood posters plastering the Mumbai city walls and Amar Chitra Katha comic books from her childhood—and the poster-sized comic book moments re-visioned in the Pop Art of Roy Lichtenstein.

In the 1990s, Siona began a series called Finding Home—reflecting on “home” and its implications, particularly for an itinerant, not only as a matter of moving between physical locations, but of becoming comfortable with diverse cultures.

“Home” is being comfortable in one’s own skin—a psychological metaphor literalized by her figures’ blue color. The blue sky is shared by everyone—and popularly associated with Krishna, a male god. Applied to female figures, such blue pigment asks the viewer to rethink gender categories. The Hindu idea of Ardhanareshwara (Shiva and Parvati as one bi-gendered being) merges with the kabbalistic idea of the Shekhinah: the female aspect of the genderless God residing in everyone when we are “gender-balanced” in our being.

Ultimately, Siona’s lush, intensely trans-cultural art seeks to be part of the process of improving the world, not merely observing it. A small 2000 gouache and gold leaf work—#46 in the Finding Home series and entitled Tikkun ha-Olam—offers a concise statement of this intention. The Hebrew phrase Tikkun Olam—“repairing/fixing the world,” most emphatically associated with Isaac Luria’s 16th-century kabbalistic community in Tsfat, refers to our obligation to leave the world a better place than the one into which we were born.

Siona’s Krishna/Kali-style figure dances on a lotus that is also a burst of light, with seven arms raised upwards to suggest a seven-branched menorah—the most persistent symbol across Jewish art. The arms terminate as stylized Islamic hamseh hands yielding to flames. In the spaceless background space, tikkun ha-olam is written in Hebrew and in transliterated devanagari script. The Jewish and Indian parts of the many elements defining the artist’s world offer a perfectly balanced figure: at once self-portrait and the portrait of everywoman and everyman.

Ori Z. Soltes teaches at Georgetown University across a diverse range of disciplines.

Reflections

Turning blue

According to Siona, why is her figures' skin painted in a blue pigment? What does it mean to be blue?

Tikkun Olam

In what ways does Siona's art represent improving (or repairing) the world rather than fixing it?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox