Divergent Soundtracks of Hanukkah: Ma‘oz tzur from Italy’s Jewish Ghettos

Published Nov 14, 2022

Ma‘oz tzur (Part 1/5)

Sound clip

Blessing – Ma‘oz tzur (Verona, Italy)

Mario Volterra (Cantor, 1901-1960), recorded by Leo Levi (ethnomusicologist, 1912-1982) in Bologna, Italy, on March 13, 1956, National Sound Archives, National Library of Israel, Y0156

This particular tune for Ma‘oz tzur — a Hebrew hymn written in Germany during the late 12th century by a poet named Mordekhai that is commonly recited on Hanukkah across the Jewish world — is part of a “pool” of melodies found among the Ashkenazi Jewish communities of Northern Italy. It is quite different from the one almost universally sung across the Jewish world, and it is representative of the culture of Jews who left southern Germany and Austria in the early-modern period, crossed the Alps, and settled in several Italian City States, most notably the Republic of Venice.

The melody was recorded by Leo Levi (1912-1982) as part of an effort to collect the musical traditions of the Jews of Italy, which resulted in an archive of recordings now preserved in Italy (Santa Cecilia National Music Academy) and Israel (National Sound Archives). The recording opens with the blessing recited upon kindling the Hanukkah candles, followed by the words of the Ma’oz tzur poem. While this melody is specific to the Ashkenazi ritual of Verona, Italy, other similar versions were recorded by Levi in Ferrara, Gorizia, Casale Monferrato, and Turin, attesting to its longevity among the Ashkenazi Jews of Italy.

Ma‘oz tzur (Part 2/5)

Score

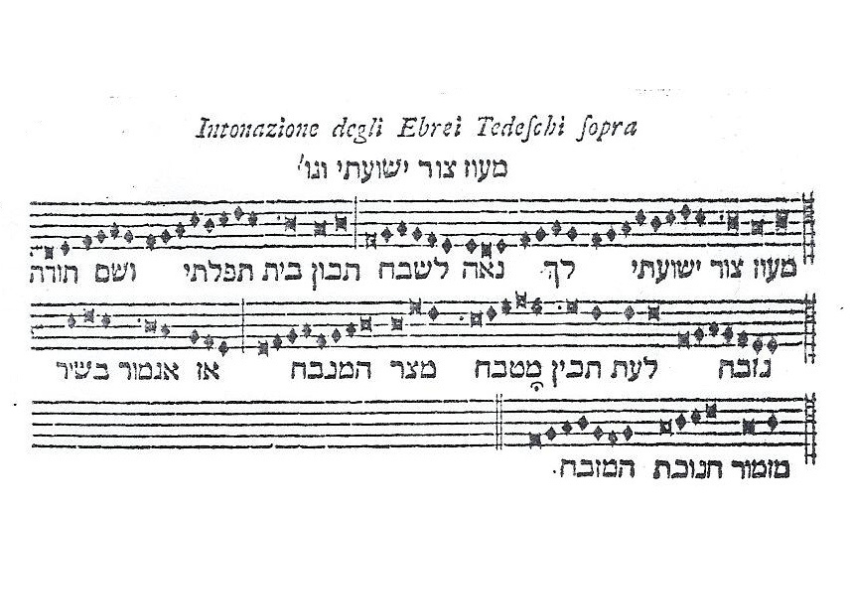

Benedetto Marcello (Venice, 1686-1739)

Estro poetico-armonico

Venezia, Domenico Lovisa, 8 vols., 1724–1726

Vol. 3 (1724), p. XI

Source: IMSLP (public domain)

Transmitted for centuries via oral tradition, this melody was first documented in writing in the 18th century by Benedetto Marcello (Venice, 1686-1739), a non-Jewish composer who conducted fieldwork in the Ghetto of Venice (the place where the word “ghetto” comes from), transcribing in musical notation synagogue songs he referred to as “Psalms.” Marcello published his musical transcriptions in Estro Poetico-Armonico, and used them as inspiration for his own original compositions. Thanks to Marcello’s publication, we know that this way of singing Ma‘oz tzur has not changed much for at least the last 300 years (and, likely, longer).

Ma‘oz tzur (Part 3/5)

Ma‘oz tzur, in the original Hebrew and in English translation, is one of the better-known, and beloved, texts of the Jewish tradition. Just like some songs from the Passover Seder, it is sung at home, often in a family setting, as well as in communal settings, and is closely associated with special foods and ritual customs. And, just as is the case for most Jewish songs across the Jewish world, Ma‘oz tzur is sung to many different melodies, both ancient and modern, including the one from Italy. And yet, none of these is as well known as the one universally sung in the United States, Israel, and elsewhere: a beloved melody, also of ancient and multi-layered origins that speaks to overlapping Jewish and Christian musical cultures in Europe. It requires no introduction, and has been recorded many times, like in the flamboyant rendition that cantor, singer, and actor Moishe Oysher (1906-1958) included in his 1950s album, Chanukah Party (above).

Ma‘oz tzur (Part 4/5)

Example 1 Above: Zamir Corale (arranged by Hugo Chaim Adler, conducted by Matthew Lazar at Merkin Hall, 2019).

The 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia provided, for the first time in the English language, a wide-ranging overview of this better-known version, on the basis of research by the 19th-century German Jewish music pioneer, Eduard Birnbaum:

The bright and stirring tune now so generally associated with Ma’oz Ẓur serves as the “representative theme” in musical references to the feast […]. Indeed, it has come to be regarded as the only Ḥanukkah melody, four other Hebrew hymns for the occasion being also sung to it […], as well as G. Gottheil’s paraphrase, “Rock of Ages”… [It was] identified by Birnbaum as an adaptation from the old German folk-song “So weiss ich eins, dass mich erfreut, das pluemlein auff preiter heyde”… widely spread among German Jews as early as 1450. By an interesting coincidence, this folk melody was also the first utilized by Luther for his German chorals… The earliest transcription of the Jewish form of the tune is due to Isaac Nathan, who set it, very clumsily indeed, to the poem “On Jordan’s Banks” in Byron’s Hebrew Melodies (London, 1815). Later transcriptions have been numerous, and the air finds a place in every collection of Jewish melodies.”

And yet, it may be surprising that the musical version of Ma‘oz tzur from Italy is also quite well-known in the Jewish world, and widely sung, albeit commonly presented on the concert stage rather than at Hanukkah celebrations. Instead of referring back to the oral tradition, its performances are invariably inspired by the transcription by Benedetto Marcello, which has been re-published many times since the 18th century (most notably, by the above-mentioned Birnbaum, and by the Jewish musicologist Abraham Zvi Idelsohn), and re-arranged, performed, and recorded by Jewish and Early-Music ensembles.

Given that Jewish music is primarily an oral tradition, the fact that a written version of a traditional melody is indeed a fascinating development, which points to the fact that, at least on the concert stage, a written source tends to be considered more reliable and “authentic” than one handed down by oral tradition.

Ma‘oz tzur (Part 5/5)

Example 2 Above: Frank London, Maoz Tsur (feat. Karim Sulayman & Sveta Kundish), from the album Ghetto Songs, 2021.

I chose to focus on the archival track recorded in the 1950s not only to showcase the diversity, and divergence, of global Jewish sounds, but also, and perhaps more importantly, to point us to the divergence in the interpretation of Jewish texts that characterizes Jewish culture. In the realm of Jewish music, each oral version of a tune invariably opens up a new world of understanding and of hermeneutical possibilities that cannot be expressed with words alone.

Francesco Spagnolo is the Curator of The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life and an Associate Adjunct Professor in the Department of Music at the University of California, Berkeley. A multidisciplinary scholar focusing on Jewish studies, music, and digital media, he intersects textual, visual, and musical cultur...

Reflections

For readers of Jewish texts:

Do you ever try to “sound” Hebrew words in your head? How do your sounds diverge from those sung by others? How do you think they reflect the individual or collective interpretation and understanding of the text?

For anyone celebrating Hanukkah:

How much do you take what is done by others – family elders, communal leaders, etc. – as a “tradition” (aka, something handed down to you and somewhat immutable)? In the case presented here, what do you feel is more “authentic”: written music or a later archival recording?

For artists (not only musicians):

What do you consider a “primary source” in Jewish music (and more generally, art)? How do you select these sources in inspiring your interpretation? What role do archives (both living archives, and those stored in public and private repositories) play in your craft?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox