Black Jewish Culinarian Michael W. Twitty Finds Common Ground in His Identities

Published Oct 19, 2022

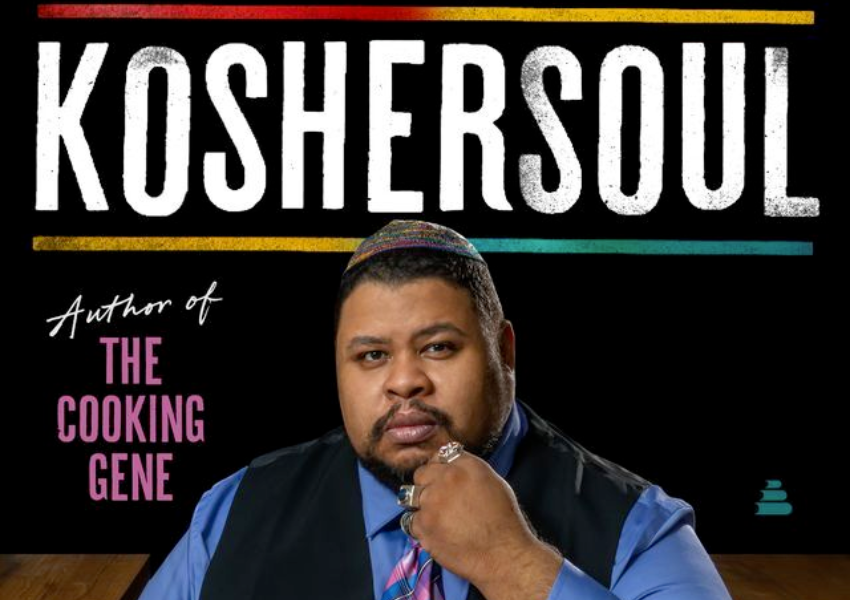

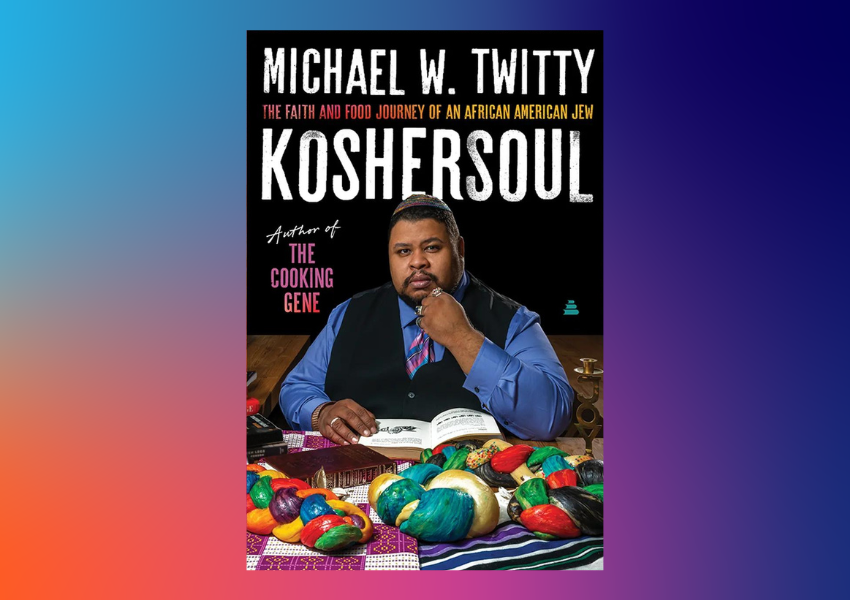

Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew

In a recent Jewish Book Council program featuring Jewish and Black culinarian, Michael Twitty, in conversation with cookbook author and food historian Adeena Sussman, declared, “I’m fighting this attitude that there’s an antipodal relationship between Black and Jewish culture.” The fight is personal for Twitty, a culinary historian and accomplished cook who is an observant Jew, tracing his lineage to African countries such as Ghana, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Senegal. Twitty won the 2018 James Beard Book Award for his book, The Cooking Gene: A Journey through African Culinary History in the Old-South. Throughout that first book, he posed the complicated question of who owns southern food. He told his family history through stories of the foods that carried them through the Middle Passage up to contemporary times.

Now comes Twitty’s second book, Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew, in which he brings together his Black and Jewish and queer identities in a challah-like braid. In fact, Twitty poses with rainbow challot (plural of challah) on book’s cover. Clocking in at 360 pages, the book is a fascinating, albeit at times, dense read. Focusing this time on Black-Jewish connection, Twitty calls up personal and universal histories to highlight Jewish lineages in Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean, South America, and Europe. In addition, he shares his affinity for Black Jewish communities in the U.S., including those in Harlem, Chicago, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Twitty also further honors the population of enslaved Black people who cooked Jewish food for their masters.

Throughout the narrative, Twitty weaves the story of his conversion in 2002, his experiences as a Jewish educator, and his Jewish practice. He says that as a Black Jew who wears a kippah (a yamulka or head covering), waiting for a bus, he can be vulnerable to racial epithets and even physical violence. Within the Jewish community, Twitty has encountered microaggressions in which people did not greet him with a “Shabbat Shalom” or asked if they could help him when he attended a new synagogue. He told Sussman, “I wasn’t your guest at Sinai. My soul was there too.”

In the preface to Koshersoul, Twitty tells of a fellow African American food writer who asked him if he had traded Black food for Jewish food. Twitty replied, “What you’re holding is the second in a three-book trilogy about the intersections between food and identity.” Twitty says he never intended to write “tomes of recipes that we could quickly lose among the many. I want to document the way food transforms the lives of people as people transform food.” Twitty writes that he uses food as his primary lens “for navigating my citizenship within the Jewish people and my birthright as a Black man in America.”

In a chapter entitled “Kappa’ed While Black: Being a Black Jewish Man,” he credits a friend, who is also a Black Jew by choice, for showing him that “I could be Black and wear a kippah and a tallit katan (the small prayer shawl with ritually knotted fringes that people wear under their shirts), in public and not be anything but normal. Knowing [my friend G] brought me to being Jewish.” Another Black Jewish friend offers, “I am an African American Orthodox Jew, and thus, a veritable cornucopia of racial, social, religious, and generational trauma.”

In an interview with The Times of Israel, Twitty said he occasionally felt as if he was “living in a constant venn diagram, in a constant place of many worlds. It’s not that complicated because a lot of people live that way, but it can be really exhausting to deal with other folks’ interpretation of that.” He notably finds similarities between Black and Jewish people in the interplay of exile and the yearning to return to a homeland. Twitty features the voices of prominent Jews of Color, including: Tema Smith, director of Jewish Outreach and Partnerships at the Anti-Defamation League, Boston-based Yavilah McCoy, founder of Ayecha, a nonprofit providing educational resources for Jewish history and an advocate for Jews of color, Shais Rishon, an Orthodox rabbi, and activist who goes by the name of MaNishtana, and Chava Shervington, a Black Jewish activist and board member of the Jewish Multiracial Network.

Twitty further posits that Black and Jewish food has been in proximity throughout history. Black and Jewish people have orbited around each other for centuries. He observes that the Jewish narrative is a sweeping arc, whereas Black people have pieced together fragments of their experiences, creating a mosaic of ancient journeys.

He also dedicates a chapter to the story of Western Sephardic migration, documenting the culinary influences of Western and Central Africa, with Afro-Caribbean traditions. This array of cuisines is frequently found at Twitty’s Shabbat table. On Friday night, he often serves kasha varnishkes alongside collard greens flavored with lamb bacon, fulfilling the laws of kashrut. He celebrates his “kosher soul” in this distinctive fusion of cuisines. He feels close to Sephardim and attends a Sephardic synagogue steeped in Middle Eastern and North African customs.

Although Twitty insists that Koshersoul is not a cookbook, it has an appendix of 50 recipes for foods such as koshersoul collards, Louisiana-style latkes, Ethiopian Berbere Brisket and a charoset from Suriname whose recipe calls for seven fruits. Twitty’s dynamic and extensive inventory of recipes highlights his conviction “that our plates are constantly shaped by everything we encounter and everything in us.” This impressive collection of recipes also creates a unique history tracing Jewish and Black food.

If The Cooking Gene was Twitty’s homage to the table he elegantly set for his enslaved ancestors, then Koshersoul pays tribute to Jewish history and the diversity represented in the foods he prepares for his Shabbat table. After all, Twitty is a proud citizen of both cultures.

Click here to find Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew at your local library.

Click here to buy Koshersoul: The Faith and Food Journey of an African American Jew.

Listen to an audio sample.

Jewish Book Council Presents "Koshersoul: A Conversation with Michael W. Twitty and Adeena Sussman"

(59 min) Join Jewish Book Council and best-selling author Michael W. Twitty in a conversation about identity, food, culture, and intersectionality. Koshersoul is a thought-provoking memoir that looks at the creation of African-Jewish foods as a result of migration and the diaspora. Michael Twitty will be joined by Adeena Sussman, food writer and author of the upcoming book Shabbat: Recipes and Rituals From My Table To Yours.

Michael W. Twitty is a noted culinary and cultural historian and the creator of Afroculinaria, the first blog devoted to African American historic foodways and their legacies. Twitty has appeared throughout the media, including on NPR’s The Splendid Table, and has given more than 250 talks in the United States and abroad.

Adeena Sussman has co-authored eleven cookbooks, including the New York Times #1 bestseller Cravings—and its bestselling follow-up Hungry for More—with Chrissy Teigen. She is also the author of Tahini. She moved to Israel in 2015 and lives footsteps from Carmel Market. She has written about Israeli food for Food & Wine, The Wall Street Journal, and many others. Her forthcoming book is Shabbat: Recipes and Rituals from My Table to Yours.

Judy Bolton-Fasman is the author of ASYLUM: A Memoir of Family Secrets from Mandel Vilar Press.

Reflections

Uncover

How familiar are you with your cultural culinary history? Are there any dishes or recipes that feel like they might intersect with other cultures?

Reflect and share

Twitty's friend offers the idea that he is a "cornucopia of racial, social, religious, and generational trauma". Think about your own cornucopia or venn diagram of identities. What does it look like? What shared ideas or traditions sit in the intersections?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox