Aviva vs The Dybbuk: Q&A with Author Mari Lowe

Published Oct 6, 2022

Aviva vs The Dybbuk: Q&A with Author Mari Lowe (Part 1/3)

In her debut novel Aviva vs. the Dybbuk, Mari Lowe uses the figure of the dybbuk from Jewish tradition as an anchor between open reality and her protagonist Aviva’s inner world. In a MG novel deeply rooted in a community of Orthodox Jewish women, Mari Lowe explores psychological and emotional realities around our inner lives. After her father’s death, Aviva’s familiar world fractures: her Ema heads into a deep depression and goes from working as a teacher to working in the old mikvah, Aviva faces her best friend drifting away from her, and, beyond that, she’s the only one able to see the dybbuk who wreaks havoc in the mikvah. But is it the dybbuk who scrawled a hateful symbol in the wet cement near the synagogue, or someone else? Is Aviva truly isolated, or does she still have a place in her community? And is there anyone she can really talk to?

This Q&A with author Mari Lowe has been edited for ease of reading.

DRF: It’s an astonishing choice to choose the largely hidden space of the mikvah sometimes approached as almost shameful, as one of the main spaces for the action in a novel. How did you fix on the mikvah as such a central locale for the book?

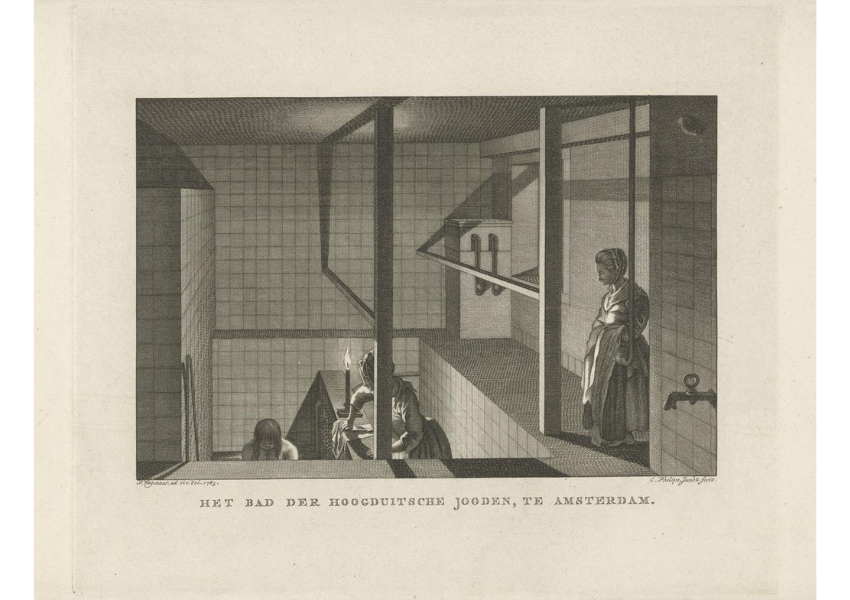

ML: It’s funny– I have a few students who have found out that I wrote a book and have been asking for the title for weeks. I can’t give it to them because the mikvah is so much of the story, and I don’t know what their parents are comfortable with them knowing about it! I don’t think that the mikvah is shameful, exactly, but it’s something intensely private to so many Jewish women– discussed freely solely in women-only spaces and kept from children. And that lends a certain mystique to it, something that would make it a mystery in itself to girls who are on the verge of Bat Mitzvah and that kind of mini-womanhood that comes with it. At the same time, a mikvah is a kind of liminal space– a place visited first at dusk, a place between ritual purity and impurity, a place that exists quietly, tucked away in discreet buildings that are visited only when we are in that in-between place. I thought a lot about liminality when I wrote this book, because it’s where Aviva and Ema are– trapped in a holding pattern where they can’t quite move forward, still lost in the tragedy of their past and in limbo since. It’s why I picked a dybbuk as a major character and a mikvah as the setting– two other things that exist in that in-between place along with Aviva and her mother.

(Continued on next page.)

Aviva vs The Dybbuk: Q&A with Author Mari Lowe (Part 2/3)

Above: Print of the mikvah in the Ashkenazi synagogue in Amsterdam, 1783. Print by Pieter Wagenaar.

DRF: Aviva struggles with accessing her need for her mother, who struggles with a deep depression, but remains assured of her mother’s enduring love for her and her love for her mother. Was this balance and struggle something it was important for you to demonstrate? Is it something you’ve observed in your own community and life?

ML: I found that I related more to Aviva’s mother than to Aviva herself when writing this element of the story. There is a painful ache to knowing that you love your child but there is something within your blood chemistry that makes you inadequate as a caregiver right now, that makes you fall short of what you want to be for your child. And at the same time, Aviva knows it and fiercely rejects it because she’s so loyal to and protective of the mother she loves, regardless of Ema’s flaws. That in itself becomes debilitating, because she does need more from her mother than she is getting, and the understanding that she offers her mother for her mother’s situation is understanding that she’s afraid to grant herself for her own situation. I didn’t want to minimize either character’s struggles in this! Ema strains to do what she can for Aviva, and Aviva strains to be okay with that. But the one thing that isn’t difficult for them is to love each other wholeheartedly, even if that love can’t always be enough.

DRF: You use the first-person narrative skillfully to navigate how Aviva interacts with her world. Was this your first choice, or did you play with other ways of framing the lens of the story before coming to this view?

ML: The first person felt right for Aviva, both because of the setting and because of the character. First, I knew that I was writing a story for people who might not be familiar with the Orthodox Jewish community, and I didn’t want this to read as a tour from outside (here is the world, here are the characters, here are their customs and quirks and all those strange little bits of Orthodox Judaism that you’ve seen in random one-off episodes of TV…) but something more intimate and enmeshed within the community. The reader isn’t entering the story as an outsider but within Aviva’s mind, from the perspective of someone who has always lived in this community and sees it as the norm.

I also felt that it was necessary to write the story from a first-person perspective because it’s very much a story about Aviva emerging from her narrow, claustrophobic life and beginning to reach out to the rest of the world! I wanted us to be within her story from the start experience it along with her. First-person narratives are perfect for that kind of character exploration, and the style of writing that follows has grown on me since then. It allows a lot more breadth of emotion and a lot more fun with an unreliable narrator, too, which Aviva certainly is.

My experience growing up in the Orthodox Jewish community is one that predominantly involves women– women teachers, women mentors, women role models and women generally helping each other. For someone like Aviva, who has no brothers or a father, that predominance becomes exclusive. And the women of the Jewish world are so varied and wonderful and real– how could I not try to do them justice in my book?

I spent a lot of time watching people in my life for the weeks of editing and seeing what traits I might be able to incorporate. Take Mrs. Leibowitz, whom I like to consider an homage to a wonderful teacher with whom I work now who notices more about individual girls in a day than I can all year. The girls, of course, have no idea. I would also say that Ema is one of my most realistic characters, and her journey is as developed as Aviva’s within the story, even though it takes up far more space. Another character who feels very real to me is Shira, Kayla’s friend who has trouble adapting to Aviva’s presence in their friendship. I think that sixth graders are capable of tremendous meanness when they feel insecure, and she rings true to me as someone who might lash out and speak horrible truths but at her core just wants to know that she has a place. I remember having friendships like Aviva’s and Shira’s reluctant kind of truce near the end of the story, where you don’t exactly like each other but you’re resigned to the fact that you’re going to be friends anyway, a strange little interpersonal adolescent quirk.

(Continued on next page.)

Aviva vs The Dybbuk: Q&A with Author Mari Lowe (Part 3/3)

Above: A modern mikvah, My Jewish Learning.

DRF: I was thrilled reading Aviva, but sad that I had never seen this rich and real representation done for the frum Jewish community before. Why did you choose this path? Was your audience in doing so more the Jewish community or a wider world?

ML: There’s a booming world of Orthodox Jewish novels out there that remain within the Orthodox world, but very few that are written for the mainstream reader. Mainstream representations of us come from outsiders who like to portray the most recognizable, cartoonish versions of us as fact. This story was born from the frustration I felt at these portrayals of a culture that I love, warts and all, and particularly the lack of any insight on the women within it. There is a renaissance of open-mindedness blooming in the book world now, one that allows for marginalized voices to speak out at last, and I wanted to take advantage of that to introduce the world to us– the girls and women who so rarely get to be humanized outside of our community.

I would say that I primarily wrote this for the world at large, and I hope that it makes it into schools and other places where adolescents’ first exposure to the Orthodox Jewish community will be an authentic perspective. But there is also a part of me that imagines how thrilled I would have been, twenty years ago, to find a book like this in the library, about a girl who looked like me and inhabited a world familiar to me. I only hope that Aviva vs the Dybbuk will be the first of many more.

Click here to find Aviva vs the Dybbuk at your local library.

Click here to find Aviva vs the Dybbuk at bookshop.org.

Deborah Furchtgott is a children's book reviewer at The Children's Bookroom.

Reflections

Taking space

The mikvah is traditionally a private women’s space, and an in-between space. Do you think it’s important to have a private space for women, and, if so, why?

Share

One of the keys to Aviva’s growth is learning who she can confide in. A big step is trusting herself to talk to Mrs. Leibowitz. Can you think of people in your life who are excellent listeners and support you without question?

Reflect

There’s a big difference between having privacy and hiding in shame, but sometimes that feeling gets blurred. Have you had an experience where you really just needed privacy? What about one where you needed to overcome shame and invite someone else into your space?

Want more?

Get curated JewishArts.org content in your inbox